MEMOIR

A FAMILY MEMOIR -page 9

Dick Sandford came to the rescue as we tried to agree on FARM’s role. He was a quiet and retiring man but he was firm in his convictions. He had worked in Africa and the Middle East for FAO over many years and had a broad perspective.

He believed that the key to development in Africa was to empower particularly marginal communities to find their way forward making use of improved agricultural techniques rather than massive projects run by teams of government and international experts.

Dick proposed to us that FARM should:

- work with marginal communities to identify problems that might be amenable to new approaches such as improving the health of the great East African camel herds and raise the production of milk in goat herds by cross-breeding and better management.

- FARM would raise the funds to do this and field small teams of specialists to work with communities bringing to them the latest most appropriate developments in research.

- We should disseminate our successful experiences widely to influence governments, agencies and NGOs.

Both Michael and I responded enthusiastically. Michael saw the opportunity to use modern technology eventually on a grand scale, while I supported the idea of working closely with communities.

Dick then offered to help us plan and launch projects working as a volunteer. He played a major part in planning the camel, goat and forestry projects. Stephen, who was an economist and had worked for the International Livestock Research Institute, joined us later to work on our Ethiopian programme.

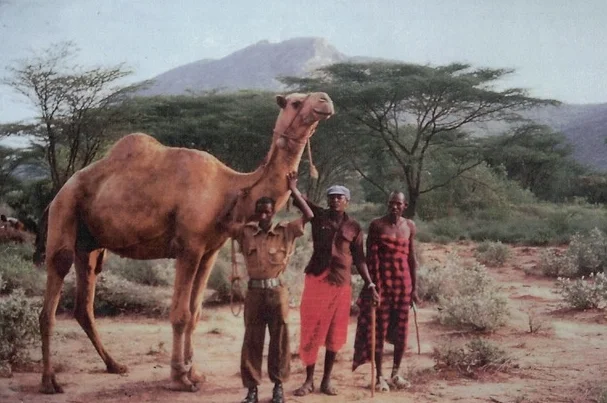

We worked in Kenya, then expanded to Tanzania, Ethiopia and finally to South Africa. Our first project was in camel herding communities. This was led by Dr Chris Field, a highly individual but deeply committed livestock specialist. We had a plane – a Cessna 206 – which enabled Chris to move from one camp to another quickly, great distances being involved.

Development work with nomadic people had previously been provided from static centres. The pastoralists were expected to come to these centres but of course frequently did not do so. Dick proposed a novel ‘mobile extension’ approach. We had two camps each with their own demonstration herd of camels. The camps would move from clan to clan, spending a month or so with each clan. Training was provided in veterinary work, and hygiene and nutrition. We also provided guidance and some funds to enable the pastoralists to set up businesses such as butcheries.

In the FARM camel project we brought in Somali bulls to raise the milk yields of the smaller lower yielding local Turkana camels.

Next, we launched a dairy goat project in Ethiopia which then spread out to neighbouring countries. Arguably our most significant contribution, this was led by the dynamic Dr Christie Peacock. This involved up-grading local goats, kept largely for meat, by cross-breeding with milk goats such as Toggenburgs and Anglo Nubians, and advice was given on growing the necessary forage and providing veterinary care.

The project was designed for poor women, particularly the many widowed in Ethiopia by the very recent civil war. The milk from the goats strengthened family nutrition and the surplus could be sold. The result was that many women began to climb out of extreme poverty.

We became involved in forestry and many other projects including a large resettlement project in Riemvasmaak in South Africa, from which the community had been forcibly cleared by the government under its Black Spot programme.

Nelson Mandela was released from jail in 1990; apartheid came to an end in 1994 but South Africa began to change radically after Mandela’s release. FARM Africa was there during this momentous period.

We had helped the scattered community with an assessment on the agricultural value of the land which was occupied by the army for training because we feared the government would claim that it had no potential for farming. I attended the meeting in the Upington town hall where the government – still the old apartheid government – was to announce its decision. The hall was crowded and throbbing with expectation. A group of burly white farmers sat in the front row clearly expecting that they would gain access to the land. The chairman called the meeting to order. ‘We have decided that the land should be returned to the community.’ A wave of surprise swept the hall. The white farmers huddled together to decide how to respond. Their spokesman stood up and in a gruff, heavy tone said, ‘We will welcome them back.’ This for me marked the beginning of a new era.

I met Archbishop Tutu on two occasions, first as Archbishop of Cape Town and then as chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. He held, in both positions, a coffee break for all the staff including drivers and sweepers. He called me out on both occasions and I had 10 minutes of his undivided attention. He has large expressive hands, a powerful jaw and great warmth. Africa owes him so much. ‘In the new South Africa the poor may well continue to be neglected,’ he said sadly.

Michael developed cancer a year after we launched FARM and he died in 1989. I felt his loss deeply. We then moved the head office to the UK to be nearer the donors. From then on, I ran the whole of the FARM programme until I stepped down in 1999.

I kept in touch with Dick after we both left Africa and frequently visited him at his farm, a small-holding run almost on African lines, near Ludlow. He died in 2009. He was one of the finest men I have known. Stephen is still with us but stricken by Parkinsons disease. Another man of great ability and integrity.

I must record the deaths of others, too. The Kenyan government would not renew Sister Annalena’s visa after the massacre and she moved to work in a Somali hospital. There she was murdered. Chris Morris, a member of our camel team, was another victim of African violence. He was murdered by car-hijackers, shot in the back of the head.

After four years, our income reached £2 million a year. In 2016, it raised £16 million and reached 1.8 million people in East Africa.

On retiring from FARM, I received an OBE from Her Majesty The Queen ‘for services to African farming’. Christie Peacock took over as CEO. The current CEO is Nico Mournard.

Looking back on FARM I feel more strongly than ever that our approach was and is highly relevant. It put faith in communities to be able to solve their own problems – with some outside assistance. It depended on committed teams working with communities, so different from many contract-workers on bilateral and multi-lateral programmes, and we acted as a witness in dangerous and oppressed places.

Lying in bed on a recent Sunday morning, I heard Michael Palin give the Radio 4 Appeal in aid of FARM. As usual he spoke eloquently. I had invited him to give his first appeal for FARM 20 years ago and he has remained a greatly valued Patron ever since. FARM continues to be marvellously alive and relevant.

I made great friends in Africa including Patrick Mutia who worked with us in OXFAM and FARM and Eliud Ngunjiri who left the Ministry of Livestock to work with us in OXFAM and then started a group to assist prisoners with resettling on release. I set up a UK group to support him but we couldn’t raise sufficient support.